Garden City Publishing Company:Garden City, New York, 1932.

pages 291 - 345

[posted by Otto Steinmayer. To Otto Steinmayer's Homepage]

IN SOME book I once read, all descriptions of scenery

and weather were omitted from the text, but inserted at the end. in a sort

of postscript, to be taken or left alone according to the taste of the reader.

This impressed me as highly considerate on the part of the author, and I resolved

to follow his good example. But when it came to the actual writing of my

own books, I weakened, for these manifestations of Nature gave me my best

chance to use the large stock of elaborate adjectives acquired during a most

expensive college course. However, I am going to follow that system

in regard to the mechanical difficulties encountered (but not hitherto recorded)

with the Flying Carpet. I've kept them out of all the previous chapters,

to touch upon—and dismiss—at this point.

This "point" is Singapore.

The Flying Carpet, still accompanied by Elly's Klemm.

had traveled from Mt. Everest back to Calcutta, and on around the marshy

coast of the Bay of Bengal. After a visit to the gilded temples of Rangoon,

we sailed down the Burma shores till we saw "the old Moulmein Pagoda, looking

lazy at the sea." Here we turned inland and headed for Bangkok, across two

hundred and fifty miles of sharp ridges and deep canyons, all smothered beneath

a dense and unrelieved blanket of steaming jungle.* [*See first paragraph,

line eight]

In Bangkok, the King and Queen of Siam gave Elly a party, but Moye and I

could not wait to attend it, as our pontoons had arrived in Singapore and

we were impatient to get them attached.

As we flew southward down the coast of the Gulf of Siam,

the thousand miles of Malay Peninsula looked beautiful and colorful enough.

However, I had painful memories of this country. I had once attempted to tramp

across the narrowest part of it during the flood season. The distance was

only forty miles, but it took three days and two nights to fight my way through

the morasses of roots and water. Now, when we crossed my old trail at right

angles, I could discern the Bay of Bengal on the other side of the peninsula.

It was hard to believe that such a narrow strip of land could once have seemed

so endlessly broad to me, afoot.

Another five hundred miles, following the beach below,

took us into Singapore.

And now for the promised difficulties!

We had our share of them from the very first. On the

third day's flight eastward from California, our engine had stopped dead

just as we were taking off from the Oklahoma City airport. It required the

most skilful piloting on Moye's part to get us back—with only two hundred

feet of altitude and no speed—into the field. The Flying Carpet's career

almost ended then and there.

Motor trouble hounded us all the way to New York.

Here we were held up three weeks while our engine was

being doctored.

Then, loading the plane aboard the Majestic, the

stevedores allowed the fuselage to swing against a ventilator and several

huge holes were the result. Disembarking in Europe, the fabric was ripped

completely off one wing. And all these damages had to be repaired before

we could "merely speak the magic name of Timbuctoo to be transported there!"

In Paris, our aileron pushrods, which had always vibrated more than they

should, began to oscillate dangerously. For four long weeks the combined

force of technicians at Le Bourget airport could not locate the cause. Then

an American aeronautical engineer, called all the way from Finland for the

purpose, found that in assembling the airplane in California, the riggers

had installed the pushrods upside down—an error by no means as obvious as

it sounds. Once found, the trouble was remedied in five minutes. Even so,

I began to wonder if my new "province" was going to be all the workshops

of the world, as well as "the clouds and the continents."

Landing in Colomb Bechar in the sand-storm, we tore the

cushion tire off our tail wheel, and rather than wait for a new one to be

shipped from London, We wrapped the rim in heavy cord and flew on across the

Sahara. When the roaring Fire Bird frightened the storks in Timbuctoo, it

still bore this bandaged tail.

In Venice the motor began to falter again, and from there

to Bagdad we sputtered along, never knowing at what inconsiderate moment it

would die away entirely. We seemed to have a jinx motor, as though our Magic

Carpet had the wrong spell cast upon it. Four separate exorcisms, even with

Moye's adept direction, failed to banish the trouble. Then, after three hundred

hours of its temperamental behavior, we threatened to throw the blasted motor

into the Tigris and immediately it reformed of its own accord and ran superlatively

well thenceforth.

So we could forget the engine. But we were by no means

clear of trouble. In Teheran the snow and frost of the hangar-less landing

field damaged our fabric to such an extent that Moye had to hasten to Bushire

for repairs. Exposure to Persian winter weather may improve oriental rugs,

but it doesn't improve Flying Carpets.

In Karachi, we found that all our Karachi-to-Singapore flying maps, which

had been sent out from London, had been received before our arrival—and returned!

We used chiefly our imagination to fly by, for the next three thousand miles.

In Agra, while we were flying upside down to salute the

Taj, a section of the main fuel tank worked loose and dumped forty gallons

of gasoline into my lap. We managed to land without catching fire; but lost

a week waiting for the tank to be repaired.

These troubles, however, were nothing compared to what

awaited us in Singapore. Our pontoons arrived there without the support struts,

which we had been told could be made "easily" in Singapore. But it took the

engineers and local mechanics from January until April to finish the work.

The delay was maddening, and the struts and their installation cost as much

as the pontoons themselves.

Three things helped make life endurable through these

twelve impatient weeks of waiting. One was the courtesy and hospitality of

the Royal Air Force, whose air-base we were using in Singapore. Another was

the support of the Shell Oil Company. Back in America, we had made arrangements

to have them supply us with fuel wherever we needed it, and to have them accept

signed receipts to be collected in New York, instead of our making complicated

payments in local currencies. In Colomb Bechar—at the isolated Saharan tank—in

Timbuctoo—in Lisbon—in Galilee—in Maan, near Petra—in Persia—in Siliguri,

where we fueled for Everest—in Burma and Malay—in short, everywhere we went,

the Shell company had supplies for us. The problem of fuel proved to be no

problem at all. We could always be sure of finding not only oil and gasoline,

but also friendly assistance, even in the outposts where Shell stations are

almost the only link with civilization. The company's officials were particularly

obliging in Singapore, doing their best to lighten the tedium of our delay.

But the third, and pleasantest, distraction from our

mechanical troubles was Elly. Following us on from Bangkok, she was persuaded

to wait with us through a whole month of our tribulations. She kept insisting

that she should fly on to Australia right away, but we wouldn't let her.

We'd put What Good Am I Without You? on the phonograph, and she'd

weaken and stay another day.

But at length she really did decide to go, and all our

efforts to hold her were in vain. Our own route, fixed for Borneo and the

Philippines, must now diverge from hers. We would not fly with Elly Beinhom

again.

We escorted her to the flying field to send her and her

"husband" on their way. For Moye and me, it was a blue moment when she said

good-by. Elly had become an essential part of our adventure. We three had

enjoyed a comradeship in which we thought and acted as one. To lose her upset

everything. She had spoiled us, scolded us, lifted us at one bound up to the

gay and gallant level of life in which she moved. And then, when we had learned

to depend on her to take care of us completely—she left us flat!

Her little Klemm took off and circled overhead. Elly

waved—and disappeared into the tropical sky.

Shortly after, we received a note from Batavia:

My dear Papas:

Batavia was easy—only six hours—but it seemed a such long time with no Flying

Carpet to keep me company. The world became very big and very empty again,

after I left Singapore. What Good Am I—without my two Papas? And what

will you do without Elly? Who will keep Moye from talking about aviation,

and who will make Dick wear his sun-helmet? I'm sure you both go to the dogs.

But I'll play St. Louis Blues for you on my phonograph each day, and

you must play Falling In Love Again for me, and love me very much.

I kiss you both on your sunburned noses—and will always stay your good child—

BEHIND US across the jade waters of the South China

Sea, Singapore was rapidly disappearing. Before us stretched a myriad jungled

islets, the tattered fringe of the Eastern continent, pierced by the arrow

of the Equator. The Flying Carpet was on its way again.

But what a changed Flying Carpet! Its undercarriage, with the fat balloon

tires which had rolled us across a hundred flying fields, had been removed,

and two twenty-foot silvery pontoons attached (at long last!) in their place.

The dry land where it had paused between flights for nearly forty thousand

miles it must now disown, and henceforth rest, like the albatross, upon the

waves.

This Floating-Flying Carpet, proud of its new seagoing

power, had cast about for new sea-tracks to travel—for destinations as lost

in the sea as Timbuctoo had been in the Sahara. We decided, first of all,

to call upon the White Queen of Borneo.

But has Borneo a white queen? Isn't it a savage aboriginal

island, inhabited only by head-hunting wild men and orang-utans? Speaking

largely, that is true. But over these head-hunters, and over these jungles

where the big apes live, there rule a white King and Queen as cultivated,

as urbane, as any in the world—with a history as romantic and remarkable.

In the year 1803, there was born in India, of English parents, a baby boy,

James Brooke. who was destined to lead a life unique in modern annals. From

childhood he had one all-consuming ideal—he wanted to make a country of his

own. And with his imagination, his powerful personality, and his zest for

fighting—qualities which became apparent as he grew—he seemed well equipped

to achieve his ambition, rash as it was.

At thirty-two, James Brooke was able, on inheriting a

small fortune, to buy a sailing ship, the Royalist, in which to pursue

his idea. He set out from England to take his vessel to strange unexplored

regions of the globe, to see what no Englishman had ever seen before, to fight

pirates, to dethrone kings—and to raise a new throne, somewhere, for James

Brooke to sit upon.

The East, at that period, was still the most adventurous

part of the world, so he drifted eastward. In Singapore he heard that the

northern coast of Borneo offered endless opportunities for exploration and

adventure; that its Malay rulers were at war with the inhabitants, and that

the whole island was harassed by pirates and slave-traders, who prevented

any development of its rich resources.

To James Brooke this promised just the exciting element

he was seeking. He set his course for Borneo. Reaching it, and finding a beautiful

nameless river debouching past a Gibraltar-like promontory into the sea,

he steered his auspiciously named ship some twenty miles up-stream. There

he came to a thatched village, which its handful of Malay and Dyak inhabitants

called Kuching

But Kuching, when he arrived, was not the peaceful place

its peaceful setting indicated. The town was in ruins; its people in rebellion

against the oppression of their overlord, the Sultan of Brunei, who lived

farther up the coast. Brooke, just to stretch his legs, went ashore with gun

and cutlass, and practically singlehanded, through moral suasion and physical

force, established order in the distracted land. The citizens of Kuching,

impressed with Brooke's air of power, insisted that he become their King

and govern them as a state completely independent of Brunei. This was the

opportunity he had dreamed about. He not only accepted, but forced the Sultan

to recognize him, and to cede him seven thousand square miles of land along

the river.

So James Brooke had a country of his own.

The next thing he did was to give his country a name—

Sarawak. Then he began to organize it and develop it. He built himself a palace—for

he felt he was there to stay; chose a council of state, created an army,

designed a national flag, and composed a Constitution which gave him and

his heirs absolute ownership forever. His subjects numbered about two thousand

partly civilized Malay townsmen, and twenty thousand head-hunting Dyaks

living in communal long-houses in the jungle.

But from the first, Brooke had to face the most powerful opposition. England

looked upon him as a menace to her interests in the Indies, if not as an actual

pirate, and withheld support. The Sultan of Brunei conspired constantly to

recapture Sarawak from this alien interloper. The Moro slave-dealers swooped

down to loot his new "capital." The Dyaks proved unruly subjects, warring

continually for each other's head, and for Brooke's, too, when he tried to

interfere. One rebellion brought about the murder of all his native officials.

In another, his palace was burned to the ground, and he himself escaped only

by swimming the river. Still a third started a conflagration that wiped Kuching

completely off the map.

But Rajah Brooke, as this resourceful one-man government was called between

revolutions, never relaxed from his original purpose of making—and holding—a

country of his own. He rebuilt Kuching. He drove out the pirates and overcame

every rebellion. And he actually managed to become leader of a British punitive

expedition against Brunei, where he captured the capital, drove the Sultan

into the jungle, and put an end to any threat of danger from this neighboring

country.

In 1864—twenty-four years after his landing in Sarawak—Rajah

Brooke's greatest desire was granted: England recognized his government,

and sent a consul to Kuching

Four years later, worn out by the cares and battles of his extraordinary

career, he died, and was succeeded— having no sons of his own, since he had

never married— by his nephew, Charles Brooke. A Brooke Dynasty was thus begun.

The new Rajah proved to be no less energetic than his

predecessor. He began to expand his boundaries by accepting the governing

responsibilities of adjoining states. Brunei became only an isolated port,

its territory having been annexed by Sarawak. At last, finding himself king

of half a million people and fifty-five thousand square miles (a country

larger in area than England itself), Rajah Charles Brooke made a treaty with

Queen Victoria which guaranteed Sarawakës independence. Only in foreign

affairs was England to be consulted, in exchange for her protection against

foreign aggression.

Secure and well governed, this new state grew out of

its savage infancy. Agriculture was promoted, slavery abolished and head-hunting

discouraged. Several other adventurous Englishmen came out to explore and

govern the wild interior. In 1917, when Rajah Charles Brooke died and his

son Vyner became Rajah in turn, Sarawak was a going concern.

Vyner Brooke had been educated at Winchester and Cambridge. But the moment

he became of age his father brought him to Borneo and made him the government's

agent in the loneliest and most savage part of the backwoods. Vyner Brooke

learned his Rajahship from the bottom rung. He fought cholera plagues among

the Dyaks; he quelled local rebellions; he learned the dialects; he explored

every inch of his father's territory. At forty-three, as thoroughly prepared

for his office as any king who ever ruled, he ascended the throne.

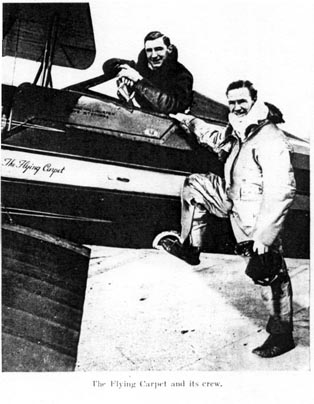

And with him ascended Her Highness, the Ranee Sylvia,

daughter of Lord Esher.

This royal couple, in their turn, have ever since ruled

Sarawak with the same wisdom and benevolence that marked the reigns of the

two previous Rajahs. Audience with them awaits any poorest, nakedest subject

of the realm who seeks the palace at Kuching. The Dyak chiefs, leaving their

smoked human heads in their longhouses' and dressed largely in beads and tattoo,

paddle down to the capital and march into the palace. There, squatting on

the floor and chewing the inevitable betelnut, they gravely place their difficulties

before the Great White Tuan, and are as gravely listened to and counseled.

Despite the intimate and paternal form of Sarawak's government,

it is taken quite seriously in Europe. Young Englishmen are always ready to

accept the Rajah's appeal to enter the service of his proud, romantic little

nation. Fully seventy-five English-born state officers are now scattered about

the country, maintaining order, and offering protection to the childlike race

of jungle dwellers who inhabit it.

It is not strange, therefore, that the White Rajah and

the Ranee, with their unique position, have become celebrated throughout

the Far East. But their position explains only part of their distinction.

They have become famous, too, for their charm, their hospitality, their democratic

manners, and, in recent years, for their strikingly beautiful daughters—the

three white Princesses of this land of head-hunters.

With such enlightened rulers, Sarawak has made great

progress since the World War—but progress without that distressing capital

"P," for the rulers are determined not to exploit the country nor to change

it from what it still remains: the native land of their primitive subjects.

What changes they have wrought are not such as to spoil the little kingdom's

character. Rubber has been planted along the coast, and an oil refinery operates,

to supply all the Far East with gasoline. Otherwise, there is little encroachment

upon the native color of the land, except in Kuching itself. There, a moving-picture

house equipped for sound (and such sound! mostly Chinese) has been given to

the citizens by the Princesses—who are themselves its best customers. A radio

station talks over the local news with Singapore. A racetrack and grandstand

ornament the park.

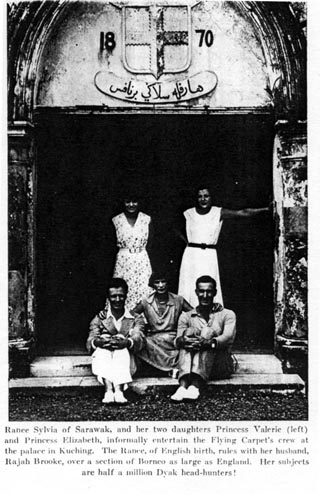

And one day, during the running of the Grand Prix, a

few months before the publication of this book, the radio excitedly called

up Singapore to tell how an airplane—a gold and scarlet airplane equipped

with huge shining pontoons—had come roaring in from over the sea, found the

racetrack, wheeled above the royal box, and lit upon the river before the

palace. It was the biggest news in months.

Having landed, Moye and I found a buoy to which we

secured the ship. Then, completely exhausted from the most trying day since

our encounter with the sandstorm on the Sahara, we stretched out on our pontoons

and waited for a boat—any boat—to pick us up.

While waiting, I was unable to dismiss from my mind the

painful things that had happened since that morning.

Back in Singapore, having little confidence in the new

and untried support-struts of our pontoons, we had not been willing to risk

the four-hundred-mile open water flight to Kuching. We thought it wiser, until

our new equipment had been proved, to court the shore as much as possible,

and approach Sarawak via the six-hundred-mile chain of islands that swings

south from Singapore to Sumatra, and from there west to Borneo. Our first

day's destination, a landlocked harbor on the coast of Sumatra, we reached

safely. The next day, still experimenting with anchors and ropes and all the

unfamiliar features of water-flying, we struck westward along the Equator,

still following the chain. It was a brilliant day—the sea, dazzlingly blue,

beat upon the little isles in rings of foam. Dense forests of palms hid every

foot of land. One quiet cove, isolated, lonely, indescribably beautiful, so

lured us that we landed on its surface, anchored, swam to the sandy beach,

and bathed in the sun for half the day.

Our goal that afternoon was Pontianak, a small seaport

on the west coast of Dutch Borneo. We found it, strewn along a river, and

came down, to the great astonishment of the community. Ours was the first

airplane that had ever been there. In an instant a hundred dugouts and rowboats

came out to welcome the Flying Carpet.

But next morning, as we prepared to fly on to Sarawak,

misfortune fell upon us.

The river at Pontianak is greatly affected by the tides.

During the ebb and flow, the current races by at violent speed. Unfortunately,

at the moment of our departure, this current was at its height, flowing seaward.

By the time I'd pulled the anchor up and cranked the engine, we were already

rushing down-stream. Moye, in order to hold us against the flow, had to accelerate

the engine. With the propeller whirling two feet away from me, I stood on

the pontoon and tried to coil up the new and stubborn anchor rope, and unshackle

the anchor. But an especially fierce blast from the propeller caused me to

lose my balance, and as I clutched wildly at a strut to keep from going overboard,

a blade of the prop caught a flying loop of the rope—and I still had most

of it wrapped around my arm. In a flash, the rope and the anchor and I were

all jerked toward the prop. Moye, hearing the banging and the clatter and

my cry, instantly cut the engine and looked around to see what was happening.

He saw the rope ripped into shreds; he saw the propeller

bent into a bow-knot; he saw the water pouring into a big hole in the pontoon

where the anchor, before it was hurled overboard, had been whipped against

it; and he saw me, with all the skin raked off my arm and hand, lashed to

the motor cylinders by the same strands of hemp which had fouled the crankshaft—my

head not an inch from the prop—and the Flying Carpet rushing helplessly down-stream,

right in the path of an oncoming freighter.

Moye, true to form, kept a cool head. Diving out of his

cockpit with a knife, he slashed the rope which, bound around my shoulders,

was sawing me in half. He didn't stop to analyze the miracles that had saved

me from the propeller—the freighter was upon us—the left pontoon was sinking

dangerously low. He waved frantically at the steamer—it veered to one side

and we scraped past. A half-dozen launches, seeing our distress, came hurrying

to our aid. One threw us a towline, and we were dragged into a side canal.

Fortunately, our pontoon had four compartments, and only

one was flooded. The crankshaft did not seem to be bent. The propeller, however,

looked hopeless. But Moye, taking blocks of wood and a blunt-headed hammer,

beat the prop out—believe it or not!—more or less straight again. And a local

machine-shop fitted a makeshift patch over the hole in the pontoon—all in

five hours.

Then, when that was done, Moye looked after me. My arm

and hand had been savagely skinned by the rope, and were swollen to twice

their normal size. But except for that (and my very shaky knees) I was all

right.

So, rather than give ourselves a chance to think about

my narrow escape, we got back in the Flying Carpet and started off again for

Sarawak, three hours beyond, with a crankshaft that might or might not be

bent, and with a propeller that was only as smooth and straight as an iron

mallet could make it.

But there was no further help to be had in Pontianak.

We might as well try to fly on toward Kuching.

Somewhat to our surprise, the Carpet flew! Borneo unrolled

beneath us again. We followed the completely wild and uninhabited coastline

around the northwest corner of the island, found Kuching, and landed in the

river.

As I have said, it had been a trying day.

But we had no time to brood over our troubles. Hardly

were we ashore when Ranee Sylvia sent us a summons to appear at the palace

that evening for the annual Grand Prix Ball.

Moye and I, dressed in our flying togs (I with my arm in bandages), accepted.

It was a memorable party.

Practically every European in the entire country—over

two hundred—had collected at the capital for raceweek, and they were all

on hand. But the Rajah himself was not there. He had gone to England with

his oldest daughter just the week before, leaving the Ranee and her two younger

daughters to receive the haut monde of Sarawak at this, the climax

of the social season.

Half-encircled by a bank of orchids, the Ranee, in white

and wearing a magnificent diamond necklace, greeted her guests, assisted by

the Princess Elizabeth, age eighteen, and the Princess Valerie, sixteen. Every

woman present was jeweled and smartly gowned in the latest (minus eight weeks!)

Paris mode; and every man resplendent in military or civil service uniform

. . . scarlet jackets, medals, ribbons. A Filipino orchestra played for the

hundred couples dancing in the great banquet hall, from the walls of which

gazed the portraits of Sarawak's Rajahs, past and present. It was as beautiful

and graceful a picture of social life as I've ever seen . . . and outside,

the head-hunters, dressed in gee-strings, watched from the lawn.

Each with a Princess on his arm, Moye and I, wearing

the flying clothes Elly Beinhom had patched together for us in Persia, led

the Grand March!

So this was Borneo!

On our arrival, we had been presented to the Ranee.

She was slim, vivacious, keenly alive.

"What a surprise you gave us this afternoon!" she said.

"When you flew over our heads at the racetrack the most important

race of the week was being run. The Rajah's horse was leading . . . but I

didn't know whether to watch the finish or look at the airplane. It was excruciating."

"I hope your horse won, just the same," I said, trying

to be gallant.

"He didn't—but nobody seemed to care in the excitement.

I've never seen the natives so agitated. We weren't expecting you—an American

airplane, unannounced, swooping out of nowhere down on top of us, out here

in Sarawak—really, it seemed almost supernatural."

"We couldn't have asked for a more royal welcome," said

Moye, looking about.

"Yes, it is fortunate that you came today. We don't dress

up like this often. You might have found Kuching dull at any other season

than race-week.... But how did you come?—where did you start from?—it's all

too amazing!"

"We started in Hollywood, Ranee Sylvia. But we came here

from Singapore. We're on our way to Manila."

"I suppose you left Singapore just this afternoon?"

"No," Moye answered ruefully. "We left three days ago.

We had a little trouble along the way that delayed us. We almost lost the

ship this morning, and Mr. Halliburton's head."

"How dreadful! Did you come down among my head-hunters?"

I explained briefly what had happened. "It was very embarrassing,"

I said. "I'm still a bit shaky. The champagne helps greatly, though. Now,

if I could only dance with you, I'd be completely revived."

You may. I always like to dance with Americans."

I was fortunate, because the Ranee was decidedly the

best dancer at her party.

We waltzed beneath a beautiful full-length portrait of

the first Rajah Brooke.

"What would he think," I asked, "seeing the present Ranee

of Sarawak at the swankiest palace-party of the year, dancing with a man in

corduroy trousers—and patched corduroy, at that?"

"I'm sure he'd be delighted," she answered, "—especially

as you are an American. He always felt friendly toward your country. It

was the very first to recognize Sarawak, you know—long before England. And

your plane, by the way, has the same colors as our flag."

What a charming person my dance-partner was. Her friendliness

gave me an inspiration:

"Ranee," I said suddenly (she was Sylvia Ranee of

Sarawak, but "Ranee" to her guests!) "—would you, as a great favor to

Stephens and me, go riding with us aboard the Flying Carpet? In spite of

the accident, it seems to be running well enough."

"Of course I would," she said, with enthusiasm. "I was

afraid you weren't going to ask me. No other woman has ever flown before in

Borneo—I'll be the first."

"We promise not to do any dangerous stunts—looping-the-loop

and all that."

"Then I don't want to go," she said, laughing.

Our invitation to the Ranee and her immediate acceptance

seemed to me to be a purely personal affair, but it almost caused a civil

war in Kuching. The government was horrified—the Ranee trusting her life

to a couple of perfectly strange foreigners who had just landed in their

midst, unbidden, unexplained, unintroduced. Perhaps we were kidnappers—"Kidnappers

in Airplane Steal White Queen of Borneo—Rajah Hurries Home—Army Called Out—Head-Hunters

throughout Sarawak are instructed not to take head of any Englishwoman found

wandering in the jungle...." The idea of such headlines in the Sarawak Gazette

only raised the Ranee's enthusiasm for this unheard-of adventure.

Presently the proposed flight was on every tongue, Malay,

Chinese, Dyak and English. Some of the younger government secretaries were

heartily in favor—if we'd flown here from Timbuctoo we must be safe enough!

The Minister of Public Works and the Chancellor of the Exchequer were also

pro-flight. But the Secretary of State and all the wives (who hadn't been

invited ) were vehemently anti-flight. What would happen in the Rajah's absence,

they asked, if the Ranee were injured? The Rajah would hold the Secretary

of State and the Minister of Health responsible. And if she were killed, the

government would be without a ruler for several weeks. There might be a coup

d'état, even a revolution. The Secretary of State threatened to

radio the Rajah to radio back to his wife and forbid her to take this foolish

risk. In fact, the secretary did just that.

"Now we've got to hurry, and have our flight before the

Rajah's cable comes," the Ranee confided in me. "I do want to fly!"

And so we hurried. The Ranee, the pro-flight Chamberlain,

and the Princesses Elizabeth and Valerie, with two Dyak chiefs as escorts,

and Moye and I, set off on the royal yacht, down-stream to where the Flying

Carpet was anchored. The Ranee, provided with helmet and goggles, climbed

into the front cockpit. I raised the anchor, cranked the engine, and climbed

in beside her. Moye, in the rear cockpit, soon rocked us off the water,

and in a moment we were far up in the sky.

Straightway we flew back over the palace and the town.

Shops and offices were emptied and all business suspended, as the entire population

rushed out into the streets to gaze up at their Ranee overhead in the flying

boat.

Sarawak looked extraordinarily beautiful from the air.

Smoky-blue jungle hiding every foot of ground . . . and the broad river winding

down from the mountains, past the neat little whitewashed, palm-shaded town,

and flowing out into the China Sea—the river up which James Brooke had sailed

in his Royalist over ninety years before, to make a country of his

own.

We landed safely beside the yacht, and delivered our

passenger back on deck—unkidnapped. She was elated over her flight, but had

some trepidations about facing the Secretary of State. The Rajah's cable

came just in time to save the situation—it insisted that the Ranee must by

no means miss this opportunity of riding aboard the Flying Carpet and seeing

Sarawak from the air!

Next day, loaded down with little presents from the royal

family, and armed with letters of safe-passage, we set sail for the interior

to call upon the head-hunters. Before turning inland, however, we circled

over the palace grounds. As we did so, the Ranee and the two Princesses ran

out on to the lawn, and waved good-by with big white scarfs. We returned them

all the salutes an airplane is capable of giving, and ended with a dive straight

toward the waving figures. At the right moment, I dropped overboard the helmet

which the Ranee had worn, and then we rose again and left the town behind.

Looking back, I could see the Ranee picking up the helmet and reading what

we had inked upon it

"LONG LIVE THE QUEEN!

From The Flying Carpet and

Its Crew."

MY FIRST encounter with Wild Men of Borneo came some

years before this visit to their native island. It happened in Berlin, where

I was visiting a circus sideshow. The Wild Men were on exhibition—dark brown,

almost black, skin; clothed only in a loin-cloth, and decorated with red paint

on their faces and wild-boars' tusks around their necks and ankles. They

were in an iron cage, before which a large crowd, fascinated by such ferocious

and dangerous savages, stood and stared. As curious as any one, I pressed

close to get a good look at the exhibits, and as I did so I overheard this

Bornean conversation:

"Sho' is hot," one savage said to the other.

"Sho' is!"

They were perfectly good Mississippi negroes, making

an easy living by this great impersonation.

My faith in Wild Men was considerably shaken by such

disillusioning experience. I wondered if, when we landed at the Dyak long-house

we were headed for, the chief was going to greet me with "Good mornin', suh!

Ain't that airyplane sump'm!"

Our objective was marked clearly on a huge chart I had

before me in the cockpit. The chart had been given to us by the Ranee, after

the officials who best knew the interior had indicated on it the long-house

chosen for us to visit, on the Rejang River at a point two hundred miles from

the sea—a long-house ruled by one of the greatest Dyak chiefs in Sarawak.

There were other reasons, too, why this house had been

recommended: Besides being one of the greatest Dyak communities, it was also

one of the most remote from civilization—very near the heart of the island.

And yet, the Rejang River and its tributaries connected it directly with the

sea. We could follow this river as a guiding thread and come down in smooth

water at almost any point. If anything went wrong with the flying mechanics

of our plane, we would be able to float the entire two hundred miles back

to the coast.

The Headman of the district, Chief Koh, made this particular long-house

his capital. He was a great favorite with the Rajah and the Ranee, despite

the fact that he had been to Kuching only once in his life. The Ranee had

urged us to visit him in order not only to meet the native ruler best able

to show us Dyak life in its richest and most unspoiled form, but also to

present ourselves as good-will ambassadors bearing a gift from the Throne.

From Kuching, with our pontoons and propeller properly

mended, we had sailed up the coast a hundred miles, come to the estuary

of the Rejang, and turned up this enormous river—a river pouring into the

China Sea a volume of water as great as the Mississippi.

For another hundred miles this vast yellow flood twisted

and turned as if trying to shake us loose; but we made every effort not to

be shaken, for on either side stretched jungle as dense and as hostile as

any in the world. The banks were the home of countless giant crocodiles.

The pythons waited in the trees above the waterside for the wild pigs to

come to drink; and the orang-utans, big as men, ruled as undisputed kings

throughout this kingdom of swamps and trees.

At rare intervals we noticed long-houses beside the river,

and an occasional government post ornamented by a log fort.

During the second hundred miles, the river narrowed greatly

and ran more swiftly as we approached the highlands. We watched carefully

for every fork and landmark, to keep our exact position clear on the chart.

Guided by that chart, we came at length to the post called

Kapit, and according to instructions from the Ranee, landed there to make

the acquaintance of the district Resident, a young Englishman. Official letters

requested him to follow us to Chief Koh's long-house, to act as escort and

interpreter. It was agreed we should depart next morning, and that as soon

as he saw we had escaped the dangerous floating logs and were on our way,

he would follow as quickly as possible in his motor-dugout, arriving at the

long-house perhaps six hours later than we.

Starting off ,again, at the appointed time, we flew for

another twenty minutes across jungle penetrable only via the river. This river-route

would take the Resident and his servants, in the most modern conveyance in

Central Borneo, twenty times as long as it was taking us.

Amid such a sea of treetops, the clearing on the riverbank

around our particular long-house destination marked it before we got there.

Just above the clearing we selected a broad smooth patch of water where two

rivers joined—an ideal place to alight.

But first we would announce ourselves by diving wideopen at the long-house!

In all the history of Borneo, there was probably never

such excitement, such consternation, as prevailed inside that house. Its three

hundred Dyak inmates rushed out upon the front veranda-like platform that

extended the entire length of the building, and darted about in complete

panic, supposing no doubt that the shrieking demoniac bird had come to devour

them. Some leaped to the ground and fled into the jungle. Others seized their

babies and hid underneath the house. There was pandemonium.

We had hoped that our arrival might bring these jungle

people some entertainment, and were sorry that our first appearance had frightened

them half to death instead.

So, desisting, we landed on the river and anchored in

shallow water.

Not a soul appeared.

How were we going to get ashore? The river was too full

of crocodiles to risk swimming; and anyway, there were no banks to swim to—just

a border of half-drowned branches of trees. Taxying around to the long-house

in the hope of attracting a boat seemed unwise, for we did not know what hidden

rocks the water might conceal. There seemed nothing to do but wait six hours

for our friend the English Resident to overtake us.

Then, just as we were resigning ourselves to spending

half a day on our pontoons, a dugout appeared around the bend, manned by

an extraordinarily fine-looking young Dyak. He wore only the usual red cotton

cloth, wrapped tightly about his loins. His trim muscular body, shining in

the sun and extravagantly tattooed on arms and legs, made a perfect picture

of natural grace and strength. Thick, straight, jet-black hair hung in bangs

across his forehead and down his back to his waist. From each ear dangled

a heavy gold ring, suspended from long slits in his ear-lobes. And around

his wrists were dozens of black grass bracelets.

Paddling at full speed, he came toward us, shouting and

smiling. He drew alongside our pontoons and shook our hands, talking excitedly

in Dyak and trying desperately, with gesticulations, to make us understand

that we were welcome. He explained—and we understood quite clearly enough—that

everybody else had fled to the jungle, but that he had been not only to Kuching,

but even to "Singapura," and had seen a "be-loon" (balloon, meaning an airplane)

fly there. He knew what we were, but nobody had given him time to explain.

Moye and I embarked in his dugout, paddled to the long-house and climbed

the ladder from the water's edge up to the front platform. Peering timidly

around corners at the extreme end of the house, a handful of Dyaks reappeared.

Our escort shouted at them to come and meet us—we were only Tuans

like the Resident, come in a be-loon to visit them.

Little by little, like wild forest animals, the Dyaks began to gather closer,

shyly at first, but with increasing courage and increasing numbers, until

presently three hundred brown bodies were swarming toward us from the jungle,

from the branches, from the hillside above. It finally became a race to reach

us—and the naked little children, agile as squirrels, got there first.

We looked about curiously at our new friends. They were

all full blooded Dyaks—surprisingly small, but surprisingly beautiful. The

men were dressed uniformly in red loin-cloths and narrow aprons, heavy earrings,

anklets and wristlets of twisted grass. The women were dressed as simply—bare

from the waist up, with their hips wrapped in a single cotton cloth. A few

of them Wore high corsets made of rattan hoops wrapped in copper wire, fitting

snugly around their waists. They wore their hair pulled back and tied in a

knot. All the men, on the other hand, allowed theirs to fall freely down their

backs. It not infrequently reached their knees. Everybody was adorned with

the same tattoo, always dark blue in color, we had noticed on the young man

in the dugout. What agreeable faces! True, all the noses had flat bridges,

and the eyes had a slight Mongolian slant, but in their glance were quick

intelligence and appealing kindliness.

But what gave them all such a surprised expression? .

. . It was their eyebrows and eyelashes—there weren't any. Every eyelash

and eyebrow had been pulled out. Only the littlest girls were still unplucked.

We could not help observing their teeth as they crowded

around us, now talking and laughing. Each mouth was black from betel-nut;

each tooth had been filed down almost to the gums. Only the black stumps remained,

or in some cases, among what was obviously the better class, to these stumps

were fixed bright brass teeth. (Any dog can have white teeth, but only rich

people can have beautiful brass ones!) It seems hard to believe that these

disfigurements would not completely wreck their appearance. But despite all

their efforts to mar themselves, they still remained strikingly handsome.

Such physiques did not need eyebrows or teeth to compel admiration.

From out of the dense ring around us, an especially fine

figure of a man, probably fifty years old, emerged to greet us. Gray hair—deep

chest—powerful arms and legs—and a face that was as noble and as full of character

as any face I've ever seen. It had firmness about the mouth, but good humor

in the wide-set eyes. This Dyak would have commanded attention and respect

any place in the world.

He was Chief Koh.

The young man who had first come to welcome us was his

son, Jugah.

Into their hands we now put ourselves and, followed by

a small mob, were shown about the long-house.

A Bornean long-house is a community dwelling, always

erected lengthwise along a river-bank. The rear half is given over to a long

row of cubicles, one for each family, all of which open upon the front half,

which consists of one long, unpartitioned public gallery that extends from

end to end of the building and forms a sort of covered Main Street. In the

case of Chief Koh's house, this gallery was thirty feet wide and fully six

hundred feet long. Here the children play, the mats are woven, the rice is

winnowed, the drums and the blowpipes and the spears are kept; all community

life takes place here. And from the rafters of this gallery the smoked human

heads, trophies of the tribe's prowess in war, hang in hundreds.

We noticed that our entire house was lifted some twenty

feet off the ground on poles. The space below the house was used for the pig-pens

and chicken coops and as a general receptacle for all the refuse. Our long-house

was not a model of sanitation, but that did not keep it from being an amazing

structure nevertheless, considering its colossal size and the skilled craftsmanship

that had taken the reeds and trees from the jungle, and with the crudest

of implements—without bricks or stone, without saws or nails—fashioned a

cooperative apartment that sheltered three hundred people and contained all

the requirements of their village life.

That afternoon, the Resident overtook us. He spoke Dyak

like a native, and proved fully informed about this interesting and attractive

race.

At sunset, Moye and I, having learned that the depth

of the water permitted, taxied the Flying Carpet up to the crude dock before

the long-house. This gave the entire population of the place all the chance

they wanted to inspect the monster.

Old Chief Koh stood on the bank and gazed with consuming

curiosity at the winged demon. He turned to the Resident and asked several

earnest questions relative to our plane.

"Is it a bird?" he inquired. Everything that flies in the air must be a

bird. "—Does it lay eggs?"

"Yes," I said, through the interpreter, when he told

me about Koh's questions. "It is a magic bird. But it will fly only for a

special magic-maker, and only when it is roaring. If allowed, the bird will

hurl itself to the ground in order to destroy any one riding upon it. Yes—

this bird can lay eggs, too—iron eggs. They are always laid while

flying, and wherever they fall, they explode with a terrible roar and demolish

everything in sight. When you wish to destroy your enemy's long-house, you

just make this bird fly overhead and lay an egg, which falls down on the

roof and blows it up."

Chief Koh listened with open mouth, but Jugah wouldn't

believe a word of it. He knew it wasn't a bird at all. It was a be-loon.

Chief Koh's intense interest in our magic vehicle was

not without an ulterior motive. He took the Resident aside, and asked him

if it might be possible for us to fly over the long-house of the mountain-Dyaks,

fifty miles farther inland, with whom he'd been having no end of trouble

and lay an egg on the rival chief. The Resident was horrified. After all

these years of pacification, old Koh's foremost thought was still the destruction

of his neighbors. The Resident excused us by pointing out that the exploding

eggs would smash the enemies' heads to bits, and make them useless as trophies.

Koh's request, however, gave the Resident what he thought

was a much better idea—What a grand spectacle it would be for all the tribesmen

if their chief could be persuaded to go for a ride! . . . but not immediately—

not until he could collect his sub-chiefs and their retainers to watch.

Moye and I naturally responded to the idea. We'd play

it up, prepare the stage, make his flight an event that would go down in Dyak

history, make it an impressive honor bestowed in the name of the Rajah's government

at Kuching.

The Resident announced this plan to Koh and explained

that it would give him prestige beyond calculation. It would also bring to

the tribe as much glory as a successful head-hunting war. But Koh was dubious.

This seemed like invading the realm of the gods and the demons. To give him

courage, Moye led him on to the pontoons, and into the front cockpit' and

tried to explain that it really wasn't dangerous at all.

Moved chiefly by his pride, he finally agreed to fly.

And that very night, he instructed messengers to go into

the tributary rivers, carrying the fantastic story of the magic bird to all

the other tribal long-houses and their subsidiary chiefs. These chiefs must

be summoned to appear three days hence, in the morning,, to meet the Tuans

who had come there riding through the air on the magic bird that laid iron

eggs, and to behold their great Penghulu ï carried up into the

clouds and brought home again by this same monster. It was to be a very great

event. They must wear all their best feather headdresses, and all their silver

jewelry, and bring their swords and shields, and come in their war-boats with

as many followers as possible.

From the dock where the Flying Carpet was tied, a dozen

dugouts, each manned by two paddlers, pushed off to spread the news throughout

Chief Koh's territory.

SOCIAL activity began to seethe that night. Rice wine

was brought out by the jugful, and all the men, crouched on their heels in

an arc about the three white Tuans, got pleasantly drunk. In ceremony

after ceremony, we had to take part. Seated beside Koh and Jugah in the long

gallery, lighted only by the line of open cooking fires, we were fed an official

dinner. Five piled-up plates of rice were placed before us, and a tray of

eggs, fish, onions and so forth. Each of us had to garnish his own rice with

these various dressings, and in a rigidly conventional routine. We watched

Koh prepare his plate, and then followed his example. Before we were allowed

to eat it, five young, unmarried (but highly marriageable!) girls came and

kneeled before us, one girl for each, with large gourds of rice wine. We had

to drink it down as they held the gourds to our lips with their own hands.

Then a live squawking rooster was passed to us by its legs, and we had to

wave the flapping fowls over our bowl of rice and over our maiden and ask

the gods to give us the good fortune always to have a full dinner pail and

a full love-life.

All around, the men and boys sat and watched, drinking

gourd after gourd of rice wine and making comic innuendos (judging from

the boisterous laughter) about the virgins and ourselves. The women and girls

collected at a distance, but missed nothing.

This memorable scene had one other feature that I'll

never forget—the dogs. There were several dogs to each Dyak, and such

dogs!—ratlike, mangy, starved. At the smell of food they broke through

the circle like hungry flies, and snatched food from our very hands. A blow

sent them yelping, but in a moment they had sneaked back again. We had to

eat our rice with one hand—literally—and beat off the swarms of these scaly,

hairless little beasts with the other. The wretched animals never seemed

to be fed and certainly were not loved—not even wanted. But to destroy one

was considered extremely bad form. So they were allowed to multiply and starve,

accepted as a curse like the mosquitoes.

Our eating ceremony began before Chief Koh's apartment,

and was conducted by his women-folk. The moment it was over, we were moved

down the long gallery to the dining space belonging to the next family of

importance, and exactly the same meal as before was brought out, with the

same wine-bibbing and rooster-waving. To our consternation, we learned that

we must go through this ceremony twenty times, and to omit a single

gesture would be unpardonable rudeness. The rice began to swell before our

eyes, and to resist being swallowed. The wine (about twenty per cent alcohol)

began to intoxicate us. Only by pretending to eat, and by making our lovely

virgins drink not only their half the loving-cup but ours too, were we able

to finish up this gastronomic endurance test in a conscious condition.

Our sleeping quarters were in a large partitioned corner

of the chief's apartment. A bit wobbly, Moye and the Resident and I were each

led by two maidens, holding our hands, across the rickety cane floor into

this guest room. These floors were never made for two-hundred-pounders like

Moye to walk upon. His foot found a weak spot, and with a crashing and splintering

of bamboo, he plunged through the hole his foot had made. Only the clutch

of his two pretty escorts saved him from tumbling straight into the pig-pens

below.

As I undressed for bed—three pallets of mats and cotton

quilts had been prepared side by side for the three Tuans—I looked

up through the dim light shed by the Resident's kerosene lamp, and to my horror

I saw several dozen human heads suspended from the low rafters by rattan

cords, and grinning down at us—or was it the effects of the rice wine? I

tried to hide under the cotton spread, but these gruesome gaping heads kept

leering down at me through all protection.

"Is Koh at peace with the world?" I asked the Resident,

visioning a night attack from some enemy tribe eager to add white men's

heads to their collection.

"Quite," the Resident assured me. "Koh is at peace—or

at least too strong to be attacked. Anyway, Rajah Brooke has almost succeeded

in stamping out the practise of head-hunting in Sarawak—if that's what is

worrying you. Heads are still taken in the wild mountain districts along

the Dutch Borneo border; but even there the custom is rapidly coming to an

end. There are probably very few, if any, heads up there above us taken within

the last five years.

"Head-hunting is still practised by the Sarawak Army

soldiers, though. When they slay an enemy in authorized warfare, no power

on earth can stop them from decapitating their victim. The soldiers all carry,

along with their rifles, a short sword-hoping for the best. If they do

take a head in this manner, they return with it to their native long-house

and are welcomed like conquering heroes. There is a feast and dancing, and

much drinking of rice wine, and many invitations from the maidens.

"But every adult in this house can remember the old days.

Dyaks have always been the most pugnacious tribe on the island, and the most

incorrigible hunters—and any slim excuse for a war was sufficient. If there

was no excuse, they made raids anyway—just the collector's instinct! No Dyak

girl would look at a boy until he had at least one head to present to her.

"Life was cheap then. Every Dyak had to be constantly

on guard. The fighting men slept with their swords and shields beside them.

It's a true and familiar story that the man with the scaly skin disease—you've

seen several people in this house afflicted with it—was considered highly

useful as a watch-dog, because he itched and scratched all night, and couldn't

sleep. The disease actually had a monetary value. The lucky owner could

sell the infection to others who wanted to keep awake.

"Attacks on enemy long-houses were usually made just

at early dawn. Bundles of shavings were always thrust under the house first

and set on fire. As you can see, the long-houses are perfect tinder-boxes.

A fire once started underneath will consume the entire house in fifteen

minutes. While the inhabitants were fleeing down the ladders, trying to escape

from being burned to death, the attackers pounced upon them and didn't spare

man or woman. A head is a head, and its sex of no consequence when it has

been dried and smoked, and hangs from a ceiling at home.

"Naturally, there would be reprisals upon the houses

of the attackers. So it became perpetual motion. It's a wonder the Dyak race

ever survived this organized slaughter of one another. Now that the Rajah

has just about pacified this country, the Dyaks are multiplying rapidly.

Their numbers have doubled in twenty years."

"Do you suppose these heads up there are community trophies,

or the proof of Chief Koh's private prowess?" I asked.

"They are all his own. He was made a chief in his early

manhood because of his ability as a war-leader, and his ruthlessness in taking

heads. He boasts of having taken over fifty. There must be that many here—though

you can't tell how many are of women. A few may even have been chopped from

orang-utans or corpses, just to add to the impressiveness of his collection."

That night was weird and restless for all three of us.

Our ribbed cane mattress—the floor—began to leave its cross-marks. The innumerable

dogs yelped interminably, fighting for possession of the dying ashes in the

cooking fires, ashes they slept in. The pigs grunted down below. Old men,

in the long room outside, scratched and talked. The cocks began their canticle

long before daylight—and the hideous heads hanging above kept peering into

our very souls. Only the overdose of rice wine made sleep possible.

But next day was occupied with new interests and we soon

forgot our uncomfortable night.

At sunup the entire population of the long-house trooped

down to the river and bathed. However careless they may have been about the

state of their dwelling, personally they were scrupulously, almost fanatically,

cleanly. Two, even three, baths a day are the custom. They bathed in families

and in groups, as completely unconscious of their nudity as the monkeys and

the parrots that watched in the trees above.

We were seeing and learning new things every minute.

Jugah, traveled, liberated, keenly intelligent, quick thinking and quick

acting, was always by our side, anticipating, though he spoke not one word

of any language that we spoke, our every wish.

He took us into his own apartment, next to Koh's. There

we met his wife and their two strikingly beautiful little children—a boy about

three and a girl a year older. Perfectly formed, clean, lovable, they would

have taken prizes in baby shows anywhere.

It was obvious that Jugah was passionately fond of his

children. And in this respect he was typical of all Dyaks. Children are the

strongest interest in their lives. They can never have enough. Barrenness

on the part of a wife is the commonest ground for divorce. Dyaks will buy

children, steal children, do anything to get them. The occasional Chinese

one sees among the people are the result of Chinese traders selling their

own unwanted babies to baby-crazy Dyaks.

Jugah led his tribe in introducing the smartest and latest

modes of dress and entertainment. On his return from "Singapura" (where the

Resident had arranged for him to work for a season on a rubber plantation,

by way of "education") he had acquired vast tone with his new mechanical purchases

and his new wardrobe. He showed us his special treasures: Three cheap alarm

clocks—though he had not the faintest idea how to tell time by them, or even

knew what "time" meant. But the alarm part, all three going at once, brought

joy to his soul.

And then he showed us his treasured store-clothes. He had one pair of high-button,

bright yellow shoes, into which he thrust his tough prehensile feet. On his

head went a Homburg hat, so big it fell over his ears. His suit, sold to him

by some Arab trader, was a nauseating green shade and made to fit a man twice

Jugah's size. Dressed in all his glory, the young Dyak, elated as a child

in fancy-dress, paraded around the room to show Off his elegance, and asked

me to take his picture.

I could not suppress my despair at seeing such a beautiful

young animal hidden under this clownish garb. I begged him to take it off

and put on his own colorful, barbaric adornments—his shell necklaces, his

embroidered loin-cloth, his silver girdle with the carved buckles, his glorious

head-dress stuck with feathers two feet long; and to seize his spear and his

shield covered with the hair of dead enemies; to dress like the noble young

prince he was; and then I'd photograph him to his heart's content.

He obliged me, however disappointed he may have been at my low taste.

Mrs. Jugah was as grandly arrayed as her husband. Her

party dress was the usual corset, but wrapped in silver wire, and a short

knee-length skirt made entirely of beads and bells. There was a sweet soft

tintinnabulation when she moved. Mrs. Jugah also possessed the most elaborate

tattoo in the long-house. Every inch of her lovely brown body was decorated

with graceful and really beautiful designs, all done in dark blue ink. It

had taken years of pain and patience to acquire her decorations. Every Dyak

in our long-house was tattooed from head to foot; but Mrs. Jugah's undoubtedly

cost the most.

Her brass teeth also were something marvelous. At twelve

or thirteen, she had deliberately lain down, as is the custom for all girls

of that age, and allowed a Chinese pedler to draw his heavy iron file across

her teeth until they were ground off to the gums. The girls undergoing this

operation squirm and suffer, not because of the pain, which doesn't seem to

bother them at all, but because their position is so immodest!

Mrs. Jugah had gone all the way to Sibu, one hundred

and fifty miles down-stream, for her teeth, and they were worth the journey,

for upon the brass background were enameled in red and green color the suits

of a deck of cards—hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades.

While Jugah was leading the hunting and the fishing and

the dancing (alas, there was little fighting unless you joined the army),

and with his wife lending the social gaiety to their long-house, his father

was handling the departments of Government and Justice. In his hands rested

the administration of all moral and social affairs. But in Dyak-land, so simple,

so natural, are their moral and social codes, and so faithfully are these

codes followed, that Koh really did not have a great deal to do. Nowhere is

the relationship between the sexes so uncomplicated as in Borneo. The Resident,

who had lived several years in the company of these people, and had learned

to understand and to love them, explained that for Dyaks completely free

love is not only accepted, but encouraged The moment an adolescent boy feels

the attraction of girls, he "goes looking for tobacco" and loses no time

in solving the sex-mysteries. Eligible maidens sleep in the loft above their

parents' quarters—Jugah had shown us these special apartments and, with a

few sly comments and gestures, the ladder connecting the loft with the outside

world. The girl receives whom she likes when she likes. The language of love

is simple enough. For all her suitors she rolls cigarettes. Tied in one manner,

the cigarette means, "Let's talk about books." Tied in another manner, it

means, "I'm so glad you came—I'm cold and lonely." Consequently in this utterly

natural society there is no such thing as prostitution or repression.

There is such a thing, however, as maternity, but maternity

is not unwelcomed, for a girl who has proved her ability to bear a child,

has all the more reason to expect a permanent child-loving husband and a "home"

of her own. If there is any uncertainty about the father, she names the man

she suspects (or desires), and the betrothal is announced. But if the boy

rebels and refuses to marry her, he need only pay a fine equaling five dollars

in our money to the girl's family, and the case is dropped. For a few babies

by various previous lovers in no way interfere with the girl's ultimate marriage

eligibility.

Such a standard of fines is the punishment of every deviation

from a social rule. If a married man goes "hunting for tobacco" and is caught,

he must pay a one-dollar fine. If he wishes to divorce his wife, because he's

tired of her, the fine is three dollars and a half. But if he is found guilty

of their crime of crimes—incest with his aunt—the fine is the maximum—ten

dollars, a whole life's savings.

Incest is supposed to bring unfailingly a curse upon

the entire tribe. When the rice crop fails, when a plague of cholera comes

upon them, when a flood washes away their property, in short, when any dire

event happens, the chief begins to look for an incestuous cause. And so prohibited

is incest, and consequently so alluring, that he usually finds what he's looking

for. The guilty party is denounced, the fine is paid, the plague departs,

and everybody is happy.

Their rule against incest is most frequently broken by

a father or his son with an adopted daughter, and by a son with his father's

second or third or fourth wife's sisters. These sisters are all considered

"aunts" and in many cases may be the same age as, or younger than, the guilty

boy. In a natural, free-loving society, this last offense seems pardonable

enough, as there is no blood relationship. But for some strange reason the

knowledge of one's "aunt" is a disastrous, unspeakable sin—yet not so unspeakable

that ten dollars paid to the chief doesn't wash everybody clean.

On the second afternoon of our visit, Jugah gave us

each a blowpipe and a quiver of darts, such as the Dyaks use in their hunting,

and we went out to look for game along the twilit jungle trails leading from

the long-house. The power and accuracy of these pipes amazed us. Fifteen feet

long, straight, light, hollowed true? they are effective at two hundred feet.

The slightest puff sends the dart shooting forth almost faster than the eye

can follow. Jugah was a wonderful marksman. He got a wild pig on the run,

and brought down half a dozen wood pigeons from the treetops. The darts were

all dipped in poison, which, while almost instantly fatal to birds and small

animals when introduced through a wound, seemed in no way injurious to their

flesh. We ate the birds and felt no harmful effects.

Our own first efforts with the blowpipes were completely

unsuccessful. We missed everything and used up all our darts. But following

Jugah's example, we made little bullets of mud, and found those could be

fired through the pipe with the same deadly force as the darts. Jugah killed

almost as many pigeons with these tiny mud pellets as with the poisoned arrows.

As entertaining, and even more curious, was our tuba

fishing. With fish providing for the Dyaks, along with rice, the chief staff

of life, they can not be condemned for the unsportsmanlike way their fish

are caught. Tuba is a poison made from the root of a tree; and when it is

poured into a stream, all the fish die of suffocation. In preparation for

the hundreds of guests due next day, Jugah organized a first-class tuba expedition,

and we went along.

He chose a stream that had not been poisoned in several

months. A platform sloping into the water was first built across the hundred-foot

mouth of the stream. This was to catch the fish when, in their death struggles,

they came leaping down-river. Then three canoe-loads of us went half a mile

farther up, and with rocks beat to a pulp a hundred pounds of tuba root. The

juice, when mixed with water, instantly turns to a milk-white color. This

fatal fluid we poured into the stream, and with nets and spears stood by

in our canoes to capture the fish when they came to the surface.

As they began to rise, there were wild shouts of delight

from the boatmen. Jugah and his friends had fished this way a hundred times,

but from the hullabaloo they made, one would have thought this was a pursuit

as new to them as to us.

With paddles flashing and the canoes darting back and

forth, we made after the big fellows. Nets were whipped about, spears jabbed

into the water. With almost every stroke, a struggling fish was swept into

our boats. More shouts on the platform down-stream indicated that they too

were busy. The biggest catch of all was there. Fish weighing three and four

pounds were splashing about, landing on the platform, and being clubbed by

the Dyaks who, brandishing their heavy sticks, were simply dancing with excitement.

It was more of a harvest than a hunt, but it was interesting while it lasted.

We returned home with our three dugouts loaded down.

This was our contribution to the great feast that would come tomorrow.

MEANWHILE, during my own adventures and observations,

Chief Koh was busy indeed. He was expecting several hundred, perhaps even

a thousand, visitors for our Bornean flying-meet. For two days basket-loads

of rice were made ready; a dozen pigs were killed; and the fish we had caught

were cleaned and stored; and rice wine, jars upon jars of it, waited in readiness.

However apprehensive Koh may have been over his forthcoming

travels aboard the demon bird, he did not dare express his apprehension now.

But the night before, he began imbibing considerably more rice wine than usual;

and next morning, when the war-boats big and small began to pour in, old

Koh had reached a state wherein he was willing to ride on any bird that flew.

And if he had to perish in the clutches of this roaring monster—whoopee!—he

would die like a man!

Larger and larger grew the visiting company. Each moment

brought new boats and new crews. Soon there was a numerous fleet of dugouts

tied along the bank, and a dense crowd of Dyaks gaping at the Flying Carpet

still tied to the dock.

American Indians in all their war-paint and regalia were

never arrayed like these dressed-up Borneans. The jungle had been combed for

the brightest, longest feathers to be stuck in their huge head-dresses; their

bronze chests were half hidden by yards of necklaces. Many wore a small shoulder-cape

made of white monkey fur. Each brave carried his five-foot shield, a sword

in its sheath of silver, and a long slim spear. There were high spirits, loud

laughter, ardent speculation about the magic bird and what it would do, and

why Jugah went about still explaining that it was a be-loon; but this explained

nothing, for nobody knew what that was.

At last the great hour arrived. Koh stood at the top

of the ladder, drunk as a native lord can get, but still looking, with his

noble face, like a brown-skinned Olympian. The most striking thing was the

extreme simplicity of his dress. While his guests and his family were ablaze

with jewelry and fur and feathers, Chief Koh had removed every adornment,

even to his earrings. About his loins and down his thighs hung a simple black

cotton cloth. Otherwise he was undraped and undecorated.

I wondered if he knew that this simplicity gave him a

hundred times the distinction of his barbarically dressed fellows. Did he

know that when he descended the steps to meet, as he believed, his destiny,

a thousand eyes looked upon him with awe ?

We strapped the helmet and goggles over his head, and

placed him in the front cockpit. His subjects pressed close about, not even

daring to speak now—the situation was too deadly serious, too fraught with

magic and with potential disaster for them all.

I cranked the engine. The bird roared. I fastened the

safety-belt across Koh and myself, and we glided away from the dock, on around

the bend to where the Flying Carpet had first landed. Behind, like the tail

of a scarlet comet, a hundred dugouts of all sizes paddled after us. We reached

the broad water, motioned to the gallery to keep back, opened the throttle,

raced down the river and rose into the air.

I watched Chief Koh. His eyes were very big and exceedingly

anxious; he trembled, but seeing my own composure, he relaxed and even looked

overboard, grinning, at the flotilla below.

Moye kept us in sight of the canoes. Presently, taking

careful aim, he zoomed straight down, within thirty feet of them, and then

sky-rocketed a thousand feet back into the sky. The boats scattered like so

many waterbugs, but when they saw that the magic bird was only playing a

game and not dashing their chief to his death, they waved their spears and

feather helmets in wild acclamation.

We flew low over Koh's long-house. We roared up the river

at a hundred and twenty miles an hour, just skimming the waves. We raced past

the other neighboring long-houses, to give their inhabitants, too, the thrill

of beholding Koh's triumph. For twenty minutes the magic bird carried the

chief back and forth, up and down, above the heads of his tribesmen.

When he landed, he was no longer a mere Dyak chief-of-chiefs. He had become

almost a deity.

That night our long-house gallery swarmed with five

hundred visitors, all ready, eager, to pay obeisance anew to the

great Koh, who had flown through the air.

Koh himself, bursting with pride, received all this homage solemnly. He

had achieved the pinnacle. He, Koh, had done what no other Dyak had ever

done since the beginning of his race. But there would be enough broadcasting

throughout Borneo of this momentous event, without his having to talk about

it.

So he merely sat there quiet and aloof, presiding over

the feast, as louder and louder his people sang his praises.

When the time seemed ripe, the Resident asked to have

the floor. He translated to the audience of warriors the message of good-will

Moye and I had brought to Koh from the Ranee. The Resident eulogized the chief

as a conspicuous example of bravery and wisdom; and told how the Great White

Tuan in Kuching loved him and trusted him to continue leading his

people into paths of peace, and dignity, and honor. The Ranee's gift to Koh,

which we had brought with us in the Flying Carpet, was then presented—O rarest

and loveliest gift in the world!—a hunting rifle!

But Koh was not to be outdone in generosity. With striking

eloquence, he launched forth in counterpraise of the Rajah and the Ranee,

and swore eternal allegiance to their rule. He had kind things to say for

Moye and me, and to demonstrate his appreciation for the distinction we had

brought to him, he made us a gift such perhaps as no other foreigner ever

received in the history of Borneo—twelve human heads!

And still the rice wine flowed, flowed in a steady, inexhaustible

stream. The orchestra of gongs and drums and native bagpipes began to resound

through the long-house. The rice and fish and pork were brought out, piled

mountain high on wicker trays. There was no limit to the food, no bottom to

the wine jars.

Happier and happier grew the guests. They crowded around

Koh, around Jugah, around the Resident and Moye and me, pressing cups of wine

upon us, giving us their bracelets, their necklaces, as presents; offering

us their wives and daughters if we'd only come visit their long-houses.

Jugah, dressed in all his gorgeous belts and feathers, cleared a space and,

brandishing sword and shield, danced with superlative grace a wild, leaping,

shouting war dance that would have done honor to a Nijinsky. Encouraged by

the son of the chief, and animated by the wine, a dozen other young warriors

seized their spears and did their best to out-dance the prancing Jugah. Twelve

were soon twenty; one orchestra had grown to four; the shouting and singing

became almost deafening, echoing and reechoing out into the dense jungle surrounding

us.... And down upon this riotous scene looked the rows and rows of black

and grinning human heads, mocking this effort to clutch at life, this vainglorious

disdain of death; waiting for those who danced to cease their dancing and

come to join the grim society of the skulls.

It was a wild, boisterous, abandoned evening—but it was

not without its beauty, too. Whoever calls these people savage does not know

the Dyaks. Except for the smoked heads, which are after all merely their war

monuments, every expression of their nature is intensely appealing. gentler,