Fables tell us what life is really like

[New Straits Times, 4 March 1992]

If, reader, you have been faithfully following the literary page over the months, you might easily have come to feel that we guys who write here are so besotted with poetry that we hardly care to give prose more than a passing glance.

Prose at the beginning was a poor step-sister to poetry, it wasn't "literature." There were once good reasons for poetry's prestige. When people had no place to record things but their own brains, they stored things in verse because verse was a lot easier to remember than prose. A rhythmic poetic line makes us feel that an idea is handily packaged to carry and transmit.

The real problem with prose is that we see it as mere chitchat. We use it every day, unaware that our daily unmeasured speech too can have its own special style and special pleasures. Using prose is about as glamorous, or "literary," as wearing a tshirt.

The one exception is political rhetoric. You only have to look at the Sejarah Melayu to see how formal speech in the sultan's court differed from casual speech nearly as much as poetic language did.

The very earliest prose that has survived in writing is pretty dreary stuff, receipts, inventories, official letters kept on file in the archives of one Asia-minor king or another, dug up by archaeologists in this century. It was preserved for its style or thought but in that it contained facts useful to those whose business it concerned.

Imaginative literature in prose came relatively late, or rather, it took a long time for anyone to think stories in prose worth writing down. For there must have been a great deal of imaginative literature in the days of talk: family histories and histories of the race, stories of travel, and war, and the hunt--"imaginative" because all more or less true, but always with a little exaggeration, or a ghost or god or two, to make the story more interesting, or a little conjecture to fill in the blanks in the storyteller's mind. The Greek word for "story" is mythos, whence our "myth," a word that does not guarantee the truth of the tale.

Of purely imaginative literature, that is to say entirely made-up stories, fables (along with fairy tales) must be the oldest, as old as poetry or hymns. And fables are remarkable in that (despite appearances) they do not deal with anything but real life. The idea behind a fable is simple: imagine animals and nonhuman creatures like trees or even rocks and pots with the intelligence and power of speech that human beings have, and set them in motion. Nature seems to abound in personalities like the human world. We all have an opinion on the character of cats and rats. People in older times saw a lot more of nature than we do now in cities. They found in animals a wide range of characters waiting to be given a play to act.

There used to be a theory that the animal-fable was invented in India,

but that can't be true. Like poetry, fables appear everywhere.

Aesop is the traditional western inventor of fables. He is supposed to

have lived in the 6th century B.C. and to have been a slave, a fact that

shows how "lowly" the Greeks thought fables were. For the same reason later

writers had the itch to fiddle with them. Plato says that one of the last

things Socrates did before his execution was to rewrite a fable of Aesop

as a poem, having been commanded in a dream to "work on his music." Socrates

too tried to elevate the fable to a more respectable level, to make it "literature."

We do not have Aesop's original words. But the late Greek prose versions

seem to me to be close in spirit to what I imagine Aesop wrote. The very

simplicity and brevity of the language appeals to me. Aesop says exactly what

he has to say, then stops.

He does not psychologize his animal characters. We know what the animals

are thinking and Aesop doesn't take away our pleasure of seeing into their

minds. Here's one of his best known:

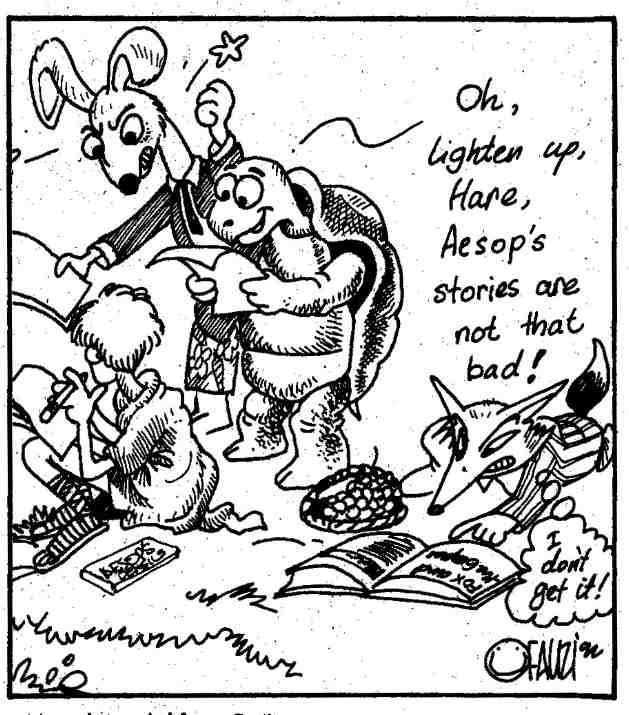

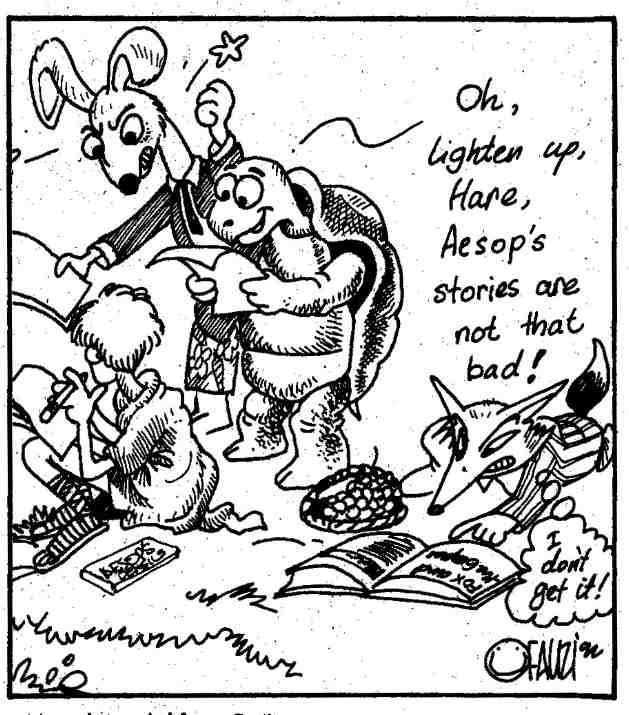

A tortoise and a hare started to dispute which of them was the swifter, and before separating they made an appointment for a certain time and place to settle the matter. The hare had such confidence in its natural fleetness that it did not trouble about the race but lay down by the roadside and went to sleep. The tortoise acutely conscious of its slow movements, padded along without ever stopping until it passed the sleeping hare and won the race.

What's amusing here is the contrast of character. The hare is arrogant,

the tortoise stubborn, determined, and slightly stupid. If you like (and

many people have), you can expand on this story's framework to draw it out

much longer. A version of this tale I heard here made heroes out of the squirrel

and the snail, and the teller amused us a lot with his touches of character.

Another:

A hungry fox tried to reach some clusters of grapes which he saw hanging from a vine trained on a tree, but they were too high. So he went off and comforted himself by saying: "They weren't ripe anyhow."

You may be asking at this point why I didn't put the morals of the fables down after them. Every fable is supposed to have a moral, right? Well, yeah. But the moral, I think, is the least part of the story. The morals that accompany Aesop's stories in the manuscripts were all added a thousand years after Aesop told them. Why bother anyway? Any sufficiently alert kid of six can tell you what the story teaches. That's his pleasure, to figure it out for himself. At the same time, no kid will confuse the lesson you can derive with the story itself. Fables were written to entertain.

Instruction alone will not hold a listener or a reader. If teaching persistence were the main purpose of the first fable... well, grim educators have invented ways of doing that more rationally. It is absurd for the tortoise and the hare even to think of holding a race. That they would actually do it is part of the fun.

As for the second fable, what moral would you put to it? My Penguin version ends: "Men, when they fail through their own incapacity, blame circumstances." That moral suggests that the fox is lying to himself. But if we take the fox's words as true, then the lesson of the story is not to waste effort getting bad results. You could come up with a lot of other interpretations.

Tiny story to suggest so many ideas! That is what good storytelling is all about, and the better the story, the harder it is to put a moral to it. Life is complex, and the fable, brief and humble though it is, does not turn life into a matter of black and white. Fables are not always entirely "heartwarming." Sang Kancil gets eaten by the crocodile as often as he outwits him.

The fable is one of the models for stories about human beings, that have

become more and more "realistic" as time has gone on. At least superficially

so. What are the characters in a novel but the fauna of our present civilization?

The fable trusts in our power to understand and interpret what happens around

us. The real moral of every fable, and of all good fiction is: "This is what

life is like. You judge."

_______________________

The two fables here are translated by S.A. Handford and published by

Penguin in Fables of Aesop.

| BACK |

INDEX |

NEXT PAGE |