Crossing the barriers between the past and us

[New Straits Times, 22 January 1992]

My columns appearing to the contrary, I have been away on holiday for two months. Now here I am again, debauched with turkey, bordeaux, and plum pudding, and my brain has lost temporarily its grasp of specifics, classical or whatever. Let's then stick to generalities, which are easier, if not safer.

After a long break---it's been two months since I read any Greek---I come back to my topic and its familiarity has dimmed. Antiquity again looks strange, and that's a good point to begin again. Perhaps you will already have an opinion on what makes a classic classic. Starting from that we can turn to other things.

Whether our respective ancestors haunted icy caves or roamed the green jungle, they surely noticed both life's limitations and the unbelievable richness of experience, and invented their own wisdom about what it meant to be here.

But we have not been around for all that long. Who knows when the human animal first began to speak and pass on their wisdom? Even if speech arrived as long as 100,000 years ago, there remained plenty for each generation to discover. Fossils show that the longest a caveman could hope to live was about 35 years, and then die while (one would think) he was still in his prime. It was a very long time before our race arranged things comfortably enough to permit people to reach old age, and then discover what that felt like.

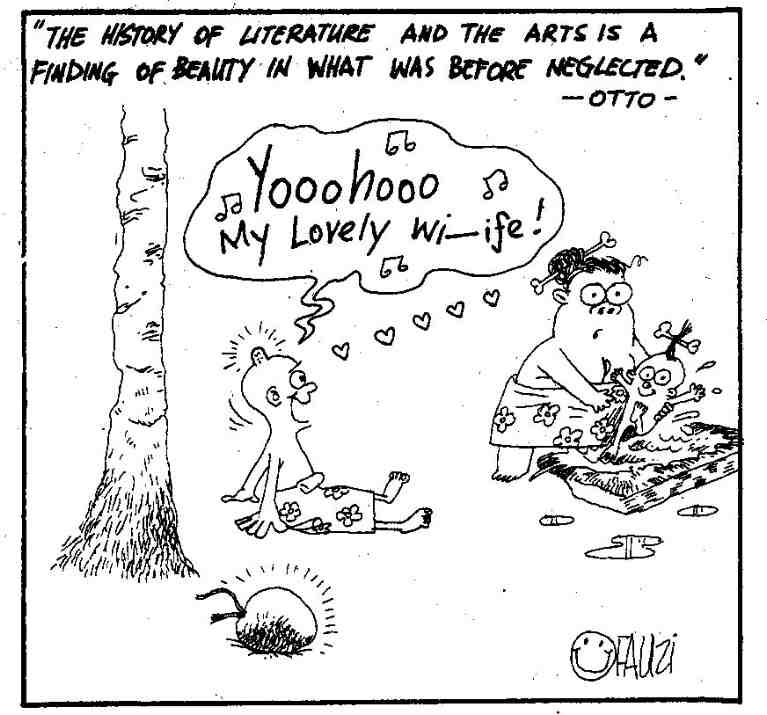

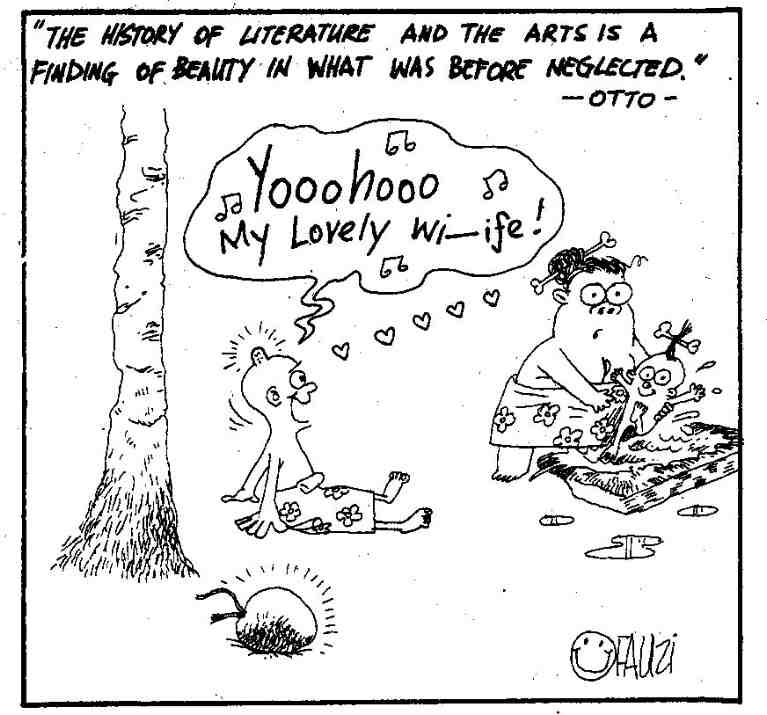

Times rolls on, and people discover things not seen or felt before. Bewildered Romans shook their heads and muttered ex Africa semper aliquid novi, "always something new out of Africa," and we could apply the same to life in general. There is always something we haven't noticed before. Maybe thousands of years ago nobody thought much of landscapes. Then, one day, someone noticed how beautiful the scenery was. The history of literature and the arts is a finding of beauty in what was before neglected or thought ugly.

The process of handing down a sensibility goes slowly by word of mouth. The invention of writing allowed people to reach many more people at a farther distance of both time and space.

Ancient writings remain fresh because they are the first attempts by anybody to formulate their feelings in a way that will carry on beyond them. They are not writing for the mere sake of writing.

Written words connect the past and the present. The more a person has

read, the better an idea he can have of all that the world has been. And

one can go back pretty far. There is enough left to have a very good taste

of what people have been thinking and feeling since the art began.

As far as writing goes, I am speaking of literature, not of its sinister

side. Most of our earliest tablets and scraps, at least in the western world,

are tax rolls, inventories, and receipts. Writing functioned at least as

much as a means of government control as of spreading enlightenment.

We are now in a new age of extremely rapid change. Within living memory,

the links with our past have been snapping, to the point that, for the first

time in history, we must cross a sort of no-man's-land in order to talk with

our ancestors.

The waste is strewn with barriers. The first of these is language. To read the past, we must master Greek, or Kawi, or hieroglyphics, or Chinese bone script. It's not just a matter of learning another set of sounds. The languages people used in the past differ radically from modern languages in the way they put ideas together, and strangely enough, the farther back you go, the more complicated gets the grammar. Sanskrit develops an overwhelming variety of language out of the endless recombination of some 700 roots. Every Greek verb can appear in over 300 separate forms, each with a separate function.

Taste, ours and theirs, also puts up another barrier. In my teaching here at UM, getting students to understand and sympathize with the styles of old English writers is, after helping them with their language, my most difficult and important job.

People of former times valued restraint, a clarifying and shaping of emotion. Traditional verse in all languages is a kind of restraint. Ancient styles of dance created beauty through discipline. We moderns like to let ourselves go, a good thing in its own way. But consider how Greek tragedy did not permit violence on stage, and how modern movies show the most graphic horrors. It seems to me that the modern style draws the emphasis away from the terror and violence of emotion and places it on the act itself, out of the soul and onto matter. The disturbing result is that violence becomes banal, a sensibility I am afraid leads to video-game wars like the one we witnessed last year.

The sheer quantity of entertainment of information and entertainment clamouring

for our attention is an especially rough obstacle to knowing the mind of

the past. To give an example, someone estimated that there is more information

in the average Sunday newspaper than the literate Englishman of 300 years

ago got in a year.

The essence of modernity is speed. We watch the shows on tv, and next

day watch other shows, discarding what we saw before. We are too impatient

to be entertained, to get to the point, to get on to the next in the pile.

By contrast, plays were performed in ancient Athens on only two occasions

in the year. It's a safe bet that the Athenians took their entertainment

a lot more seriously, not, please, solemnly, that we do.

Four years ago I was staying at my wife's kampong and, among other things,

reading Homer. After dinner the tv came on and I had a chance to rate Homer

as a storyteller against the professionals of Hollywood. One popular cop

show came off especially badly. The story seemed to whizz along at random,

the solution of the mystery left so many puzzles behind it that I felt more

annoyed than amused.

When listeners once sat around the storyteller, they felt free to question him and make him satisfy their doubts. A Greek audience would not have interrupted Homer's verse, yet Homer knew what was expected of him, and took pains to anticipate his hearers' questions. At every point in the Iliad and the Odyssey, you know exactly why each character acts and why each thing happens as it does.

Accustomed as we are to tv's abundant and disposable entertainment, do we have the patience carefully to read somebody who believed with good reason that what he composed would be the most important words we came across in a lifetime?

A final, and for some, impassible barrier to loving the ancients and their literature is the inconceivable gulf between the way they, and we live. What, for example, can Hesiod, a dirtpoor Greek farmer/poet, one of Homer's contemporaries, have to say at a space of 3,000 years that will mean anything to us? A lot of scholars avoid that question by treating his poetry as a kind of moonrock. An anthropologist or theorist must, by the terms of his profession, doubt or deny that Hesiod's Theogony communicates anything that we can know.

But on the other hand the Common Reader, as well as the true man of letters, must persist in believing, however much of an absurdity or paradox it seems, that these squiggles on the page record something important, perhaps of lasting value, for us who in the present remain their only heirs and possesors.

The Roman comic dramatist Terence said in one play, homo sum; humani nil alienum puto: "I am a man; I think that nothing human is foreign to me." The past is important because that is us. We not only owe our existence to our grandfathers and grandmothers, we in great part are them. To discover the past is also to discover ourselves.

| BACK |

INDEX |

NEXT PAGE |